Criteria

This blog assesses ERW’s performance against the CRCF’s Qu.A.L.ITY criteria, the criteria the Commission is using to determine which removal methods qualify for inclusion:

- Quantification: How do we robustly quantify the amount of carbon that has been removed?

- Long-term storage: Will carbon be durably stored for hundreds of years or more?

- Additionality: Would this carbon have been removed absent carbon finance?

- Sustainability: How does this practice affect the environment beyond carbon removal?

Definitions

Here we define several terms used in this blog. While consensus is building, these terms are not universally agreed upon across the carbon removal sector. Where possible we align with CRCF usage.

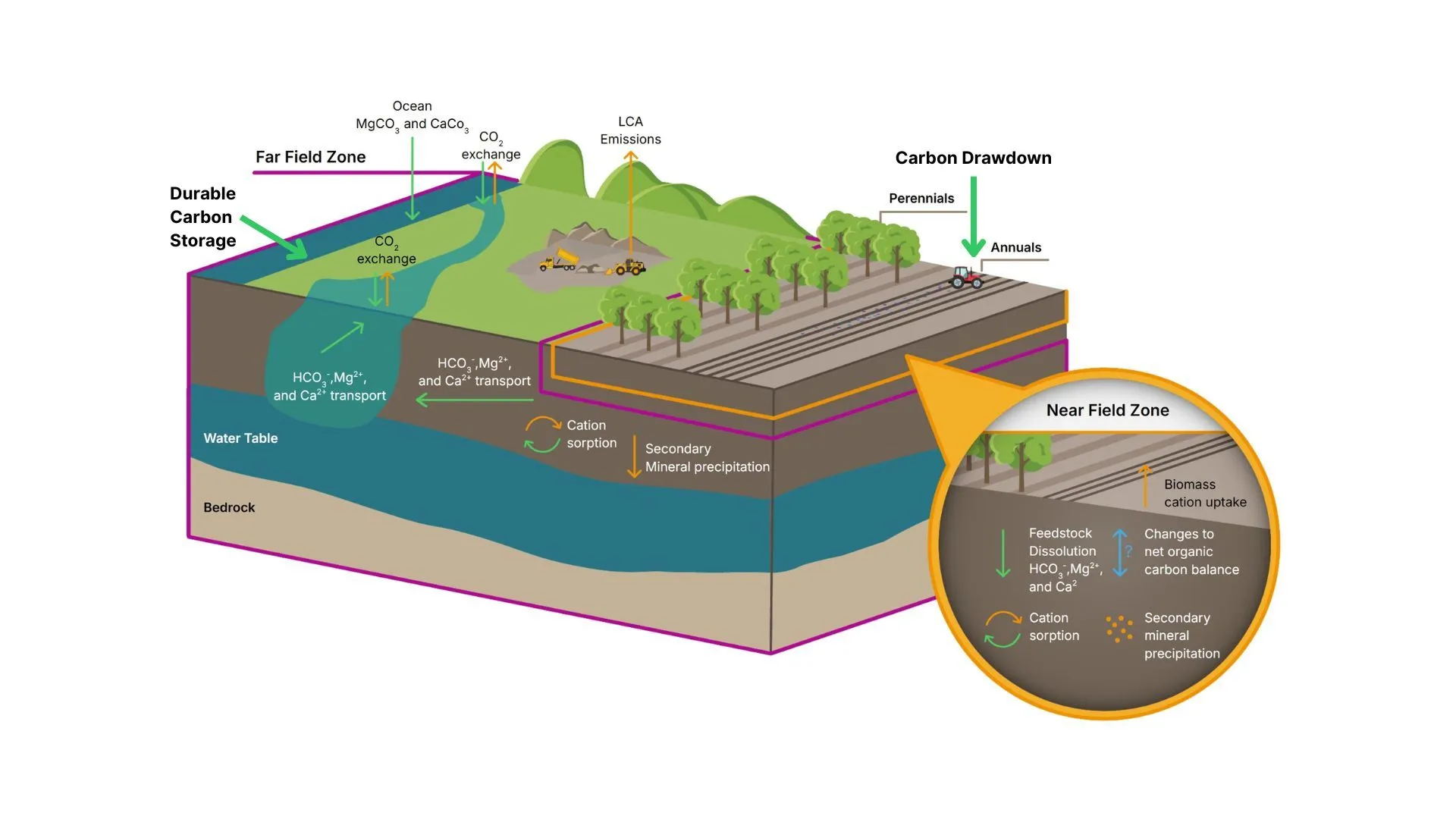

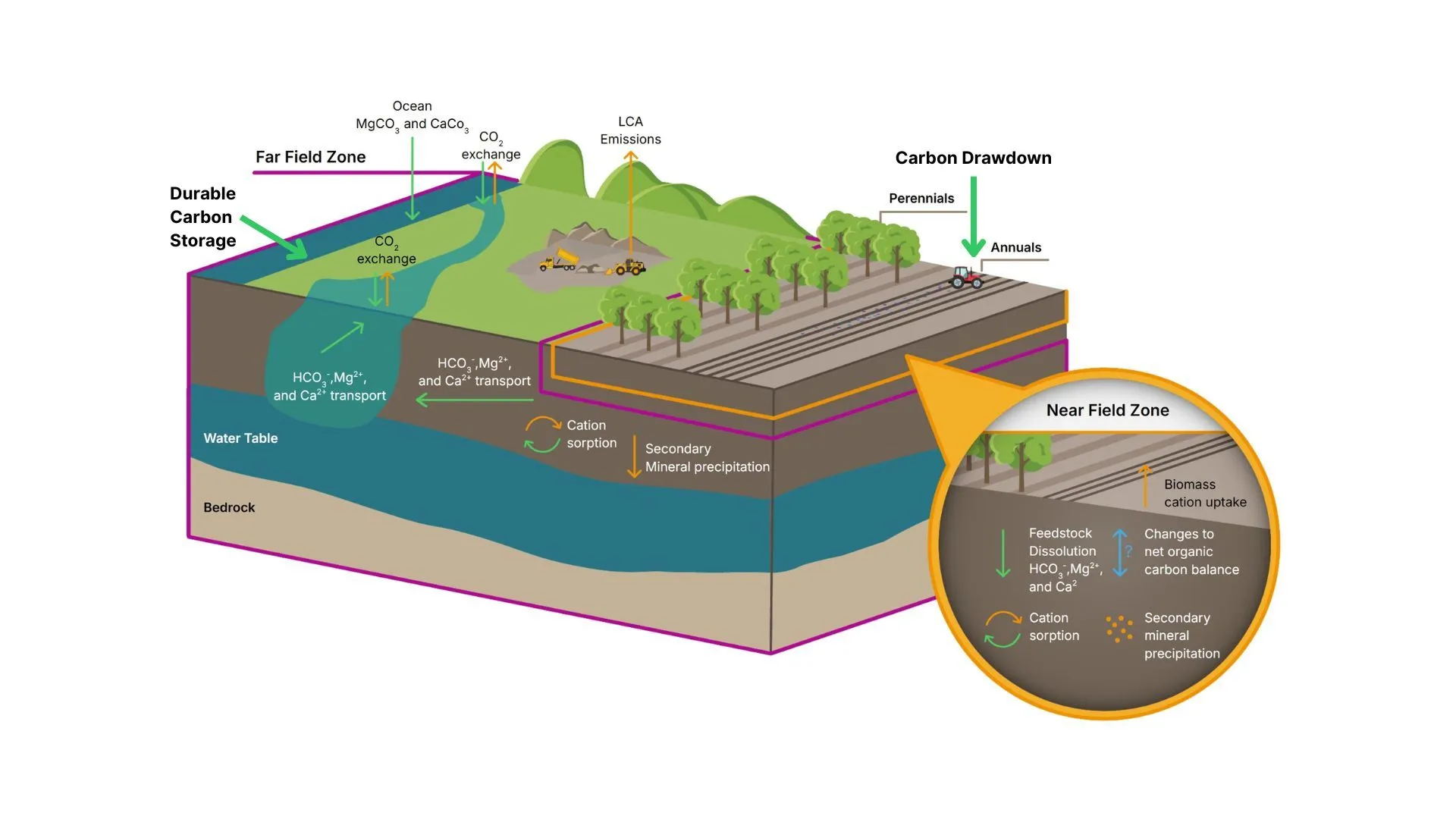

- Carbon removal (also referred to as carbon dioxide removal, or CDR): the anthropogenic removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and its durable storage in geological, terrestrial, groundwater, or ocean reservoirs. For the purposes of ERW, we find it useful to break the process of carbon removal down into two steps:

- Drawdown: the transfer of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the soil system through the chemical processes of rock weathering.

- Storage: the addition of carbon to the durable reservoir of the ocean or groundwater, where it is stored in the form of dissolved bicarbonate or carbonate ions on the order of 10,000 years or more.

Note that ERW results in carbon removal, but the two steps of this process – drawdown and storage – do not happen simultaneously. Because ERW interacts with complex natural systems, carbon-containing molecules take time to move from the atmosphere, through soil and water systems, to the durable reservoir.

- Reservoir: the durable storage location, typically the ocean (though sometimes groundwater).

- Loss: carbon that has been drawn down by reacting with applied rock, but that is lost before making it to the durable reservoir. Loss can occur through a variety of pathways in terrestrial and hydrological systems. While loss is not defined in the CRCF, we find it important to introduce this term to distinguish it from reversal.

- Reversal: the release of carbon from the durable reservoir back into the atmosphere. Reversal, therefore, can only occur after both carbon drawdown and durable storage have occurred.

Quantification

ERW accelerates the natural process of rock weathering that has regulated Earth’s climate for billions of years. Finely crushed alkaline rock is applied to fields, where it dissolves in water from rain or irrigation. Alkaline rocks include both carbonates and silicates; here we focus primarily on silicate ERW. The dissolved rock interacts with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, converting it into a dissolved form that is transported through the soil and eventually to the ocean (or, in some cases, groundwater) where it is stored for tens of thousands of years.

Quantification of total carbon removed, sometimes called net CDR, occurs by:

- Measuring total drawdown (sometimes called potential CDR)

- Deducting the following:

- Near-field zone losses: carbon losses that occur in the upper portion of the soil. These losses can be directly measured.

- Far-field zone losses: losses that occur between the upper soil region and the durable carbon storage reservoir. At current deployment scale, these losses are difficult or impossible to measure and in most cases should be modeled.

- Life cycle emissions: greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production, transport, handling, and spreading of ERW feedstock materials.

- Counterfactual carbon removal: carbon removal (anthropogenic or natural) that would have occurred in the absence of an ERW project.

For a more complete inventory of possible losses in each of these areas, see our recent blog post.

How Measurement Works in the Near-Field Zone

The “near-field zone” is the top layer of the soil, usually 15-30 cm, that is measurable over large areas with available tools. Carbon drawdown occurs in this zone as rock dissolves. A variety of tools measure either dissolved inorganic carbon (drawn down atmospheric carbon that is dissolved in water), or cations (positively charged particles from rock dissolution such as calcium or magnesium) as a proxy for carbon. After drawdown, however, carbon can be lost through a variety of pathways.

Appropriate deductions to account for this lost carbon must be made, which depend on the measurement approach taken. These measurement tools, and corresponding deductions, are widely-accepted to quantify losses in the near-field zone. However, care should be taken to ensure that the measurement and analytical approach are suited for a given soil system.

How Modeling Works in the Far-Field Zone

The far-field zone is the area between the end of the near-field zone and the durable reservoir. At current deployment scales, ERW’s impact on river and ocean chemistry is too dilute to measure, making it impossible to directly track carbon all the way to its durable reservoir. Because of this, losses of carbon from surface waters in streams, rivers, and the ocean are modeled instead of measured. These models, which draw on decades of research, are capable of producing robust and conservative loss estimations for these downstream systems (Kanzaki et al., 2023; Renforth and Henderson, 2017; Zhang et al., 2025). As our scientific understanding of earth systems continues to advance, we can expect models across earth sciences—including ERW—to continue improving over time.

Deep Soil: The Biggest Measurement Challenge in the Far-Field Zone

The deep soil, an area of the far-field zone that is too impractical to measure across an entire project, currently presents one of the thorniest challenges for ERW. As we noted in our recent blog, project developers can and should avoid deploying in places where deductions are expected to be large or difficult to constrain (i.e., uncertainty is high) based on the soil, hydroclimate, and deployment context. To further increase confidence in deep soil loss estimates, data from small, intensely monitored plots can be used to quantify and extrapolate these deep soil losses across a project site.

Conservative Approaches to Quantification

Key quantification choices can ensure that only carbon we are highly confident reaches durable storage is accounted for. Conservative quantification accepts the risk of undercounting genuine carbon removal to maintain integrity and avoid overstating climate benefits. Not all of these choices are appropriate for every deployment scenario and may evolve as ERW certainty continues to improve. Conservative approaches to quantification may include:

- Deeper measurement and extrapolation: where appropriate, using intensively monitored plots to better understand and reduce uncertainty around losses in the deep soil.

- Geographical exclusion: avoiding deployment in areas where losses are likely high or difficult to estimate. For example, certain soil types, particularly poorly-drained, clay-rich soils, can increase the risk of cation loss through mineral formation, lowering the amount of net CDR. In contrast, sandy, well-draining soils facilitate quick export of cations and bicarbonate ions from the soil, reducing the chance of carbon loss.

- Lower uncertainty bound: crediting at the lower bound of uncertainty rather than based on the mean or most likely amount of carbon sequestered. Credits can be calculated by selecting a lower error bound to credit on, such that, e.g., there is a very high chance that more carbon was removed from the atmosphere than is reported. This is one strategy for mitigating the risk of over-crediting and incentivizes practitioners to decrease the uncertainty of their deployments via careful site selection, research into new quantification approaches, and optimizing site and measurement design.

- Not accounting for likely carbon gains: disregarding additional carbon removal that happens outside of the measurement zone, even if there is a reasonable certainty that these gains are occurring as indicated by modeling.

In summary, there are several layers of conservative accounting choices that protect the integrity of ERW quantification. ERW operates within complex natural systems, making it impossible to track every atom of carbon from the atmosphere to the storage reservoir.

This inherent uncertainty does not make ERW unquantifiable; rather, it underscores the need for fit-for-purpose quantification approaches, relying on what can be effectively measured along with conservative accounting choices.

Long-term Storage

Carbon removal from ERW is considered long-term, also referred to as “durable” or “permanent”, based on a robust body of scientific evidence. The carbon removed from the atmosphere through rock weathering is durably stored as dissolved bicarbonate (or carbonate) ions in the ocean or in groundwater, on the order of tens of thousands of years. Evidence for ERW’s long-term storage is grounded in decades-long research on natural weathering, which sequesters atmospheric carbon through the same geochemical pathway.

Understanding Losses vs. Reversals

As described above, carbon removal has two stages: the initial carbon drawdown and durable storage. The risk of reversal—carbon lost from the durable reservoir—is generally low to negligible for ERW projects due to the inherent stability of bicarbonate ions in the reservoir after initial equilibration with the atmosphere-ocean system. Losses, by contrast, occur before storage and must be explicitly accounted for in net carbon dioxide quantification, as described in the quantification section.

Crediting Durable Removal

Consider a hypothetical ERW project that initially draws down 10 tons of CO₂ from the atmosphere, but loses two tons along the path to durable storage. Eight tons of CO₂ are ultimately removed, with no tons reversed. By accurately measuring the initial 10 tons and conservatively deducting two or more tons of anticipated losses, we can ensure conservative crediting. In addition, there will be an estimate of uncertainty in the CDR quantification due to possible analytical error and inherent variability in the soil system. Another layer of conservatism can be added by considering the larger error in the estimate. In this simple example, if the uncertainty is +/- 1 ton of CO₂, a conservative approach would credit seven units of CO₂.

Additionality

Additionality examines whether carbon removal would occur without intervention. It includes both financial additionality (would the activity happen without payment?) and carbon additionality (how much additional carbon is removed compared to business as usual?). Carbon additionality is often referred to as “baselining” since it compares carbon removed from the activity to carbon removed in the baseline or business as usual scenario. While we are focused on silicate ERW here, carbonates can also be used as an ERW feedstock, but often present more complex additionality considerations.

Financial Additionality

ERW demonstrates strong financial additionality in Europe. At present, silicate amendments—the most common feedstock for ERW carbon removal—are rarely applied as part of typical farm management, and the current cost to benefit ratio of silicate feedstocks is not high enough to drive adoption at a wide scale unless combined with a carbon market payment.

Baselining

Because ERW works through the action of rock weathering, weathering from other sources that would have occurred in the absence of the ERW project must be considered. For example, silicate ERW projects may displace the use of ag-lime, a carbonate rock amendment used to manage soil acidity. Carbonate weathering, which occurs when farmers use ag-lime, also has the ability to sequester carbon, albeit at a lower rate than silicate weathering.

To assess carbon removal from ERW relative to the baseline, project developers and researchers use business as usual plots (BAU)—nearby farmland with typical agronomic practices that do not receive an ERW treatment. BAU plots enable comparison of the carbon removed from ERW to the carbon that would have been removed under baseline conditions, including ag-lime in geographies where it is commonly applied. Because ag-lime is typically less efficient at removing carbon than silicate ERW, ERW typically results in additional removal, which can be quantified with high integrity through the use of proper BAU controls.

Sustainability

ERW offers significant environmental co-benefits alongside potential risks. These risks can often be mitigated through careful pre-application monitoring and site selection.

Agricultural Benefits

In areas with acidic soils, ERW neutralizes acidity, which can improve plant nutrient uptake, increase yields, and benefit farmers. ERW may even reduce the need for chemical fertilizers, which are carbon-intensive to produce. Some feedstocks also deliver micro- and macronutrients, improving plant health and potentially yields.

Managing Heavy Metal Accumulation Risks

Heavy metals such as nickel and chromium, present in some feedstocks, pose risks if concentrations accumulate (Alloway, 2013; Tóth et al., 2016; Anjum et al., 2014; Dupla et al., 2023). As rocks dissolve, metals are released; at high concentrations these may cause environmental or health impacts. Pre-application sampling of soils and feedstocks, combined with conservative formulas to project post-application concentrations, helps ensure levels remain below regulatory and human safety thresholds. In a previous blog, we recommended that—alongside ongoing monitoring— the CRCF requires project developers to take such an approach to estimate post-application metal concentrations. Cascade has developed a tool to make this process simple, replicable, and transparent.

Broader Environmental Considerations

Other human and environmental benefits and risks exist, including, on the benefit side, river and ocean acidification mitigation, and, on the risk side, localized air quality concerns from the handling of crushed rock. Project developers should conduct a comprehensive environmental risk assessment and develop a risk mitigation plan prior to deployment.

Looking Ahead

Enhanced rock weathering shows promise across the CRCF's Qu.A.L.ITY criteria. As the European Commission evaluates ERW for CRCF inclusion, the pathway's scientific foundation and scalability present a compelling case, provided robust safeguards ensure high-integrity accounting and environmental protections.

Cascade is committed to supporting this process through ongoing research and collaborative engagement.